The idea that saturated fats cause heart disease is being disproven by the day. Instead, “free sugars” are being recognized as the real culprit—and a low-carb, keto diet is the remedy

Almost everyone over the age of 60 should be taking a cholesterol-lowering statin, according to medical science. Age alone is a risk factor for heart disease because you’ve been chowing down on an unhealthy diet of saturated fats for years, and the diet-heart hypothesis blames fatty foods for the rise in “bad” LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol that clogs up your arteries.

A lifetime of eating butter, cheese and fatty meats is the problem (along with smoking or a family history of heart disease), and the bar to qualify for a statin is set low: in the US, it’s anyone over age 40 with a 7.5 percent chance of developing CVD (cardiovascular disease) over the next 10 years.

A person of any age, even as young as 25, may benefit from statin therapy, say health agencies like the UK’s NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence). NICE recommends considering statins even if the 10-year risk of CVD is less than 10 percent.

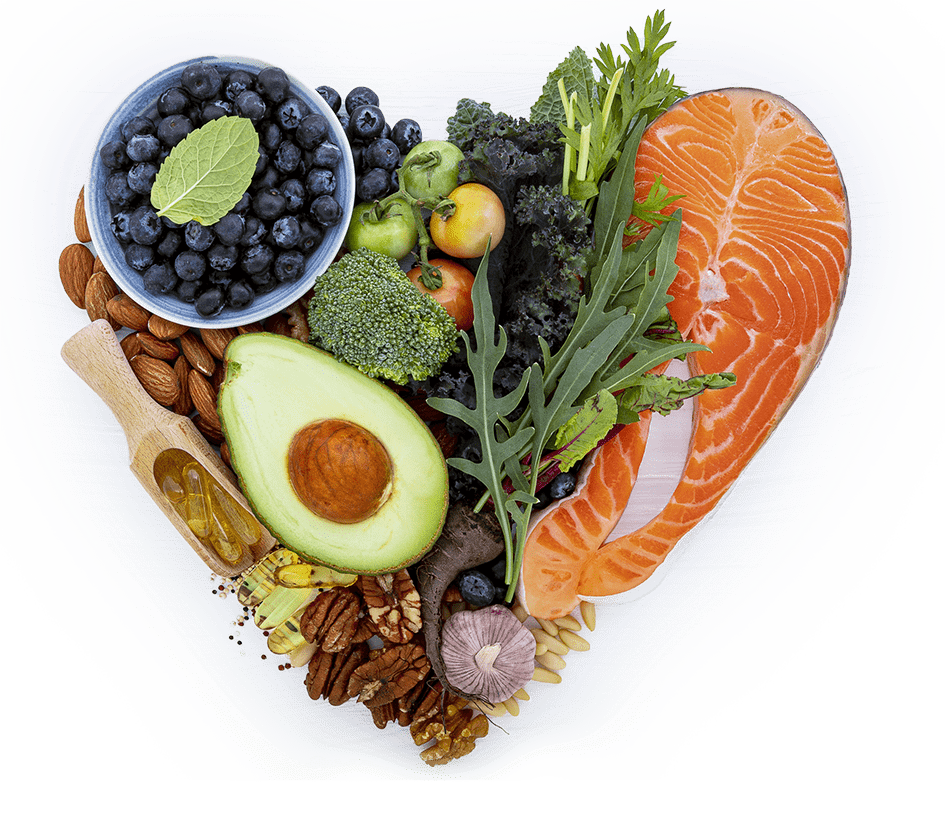

But a new study claims the diet-heart hypothesis is plain wrong. A ketogenic diet that’s low in carbs and high in fats—the very reverse of the heart-healthy diet—is one of the best safeguards against CVD, and people who eat a keto diet probably don’t need to take statins—even if their LDL score is high.1

In any event, LDL cholesterol may not be the bad guy after all. Studies are showing that people with high levels of the so-called bad cholesterol live longer and are protected against infection, some cancers and Alzheimer’s.

The researchers, Diamond, Bikman and Mason, point out that a low-carb diet is successfully used to manage type 2 diabetes, a precursor of full-blown heart disease, and that suggests it can also safeguard against CVD.

Who gets heart disease? According to the standard medical model, it’s anyone with a high total cholesterol score, and especially of the LDL variety. A high score suggests your arteries are getting clogged, which will result in atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries), the main cause of CVD.

A safe level is an LDL score under 100 mg/dL (milligrams of blood glucose per deciliter), but even this doesn’t give you a free pass; you could still be prediabetic and you might be considered a good candidate for a statin anyhow. But get to an LDL cholesterol score of 190 mg/dL, and your doctor will be reaching for the prescription pad.

With heart disease obstinately remaining the major killer in the West, doctors are doubling down on what they see as the cause—LDL cholesterol—which, in turn, is the result of eating way too much saturated fat, a theory first postulated by medical researcher Ancel Keys in the 1950s. By the time someone has reached their sixties, statin therapy is seen as the last defense against a poor diet.

Doctors so cherish the diet-cholesterol-heart theory that it has almost passed into medical dogma. Its advocates say the theory was proved by a study on people with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH)—a genetic disorder that raises levels of LDL cholesterol—who were getting CVD prematurely. The findings showed “a causal relation between an elevated level of circulating LDL and atherosclerosis,” concluded researchers Michael Brown and Joseph Goldstein,2 and they were rewarded with a Nobel Prize in Medicine for their efforts in 1985.

The study was the birth of the idea that “bad” cholesterol causes CVD, embraced by groups such as the American Heart Association and the European Atherosclerosis Society, which states that “LDL is unequivocally recognized as the principal driving force in the development of ASCVD (atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease).”

But had Brown and Goldstein hung around a little longer, a different picture would have started to emerge among FH sufferers. As patients in FH communities grow older, deaths from heart disease start to decline, and elderly FH sufferers have the same risk of CVD as the rest of the population even though they have had a lifetime of high LDL levels.3

It gets stranger still. FH sufferers are less likely to die from any disease—such as infection, cancer or Alzheimer’s—than healthy people, suggesting their elevated LDL levels are protecting them.4 FH sufferers also have lower rates of type 2 diabetes, which shouldn’t be the case as high LDL levels are a driver of the disease.5

But if that’s true, why did some in the FH group die prematurely from CVD? Diamond, Bikman and Mason suspect the real culprit is a condition known as coagulopathy, in which the blood can’t coagulate properly. The condition affected a subgroup of the participants and skewed the results they observed. Another study found LDL levels didn’t influence the risk of CVD in the FH community, but the extent of coagulopathy did.6

Doubters of the LDL cholesterol theory point out that its advocates cherry-pick the research and ignore any that refutes it. “Evidence falsifying the hypothesis that LDL drives atherosclerosis has been largely ignored,” concluded one researcher.7

If not LDL cholesterol, what? Diamond, Bikman and Mason believe the real biomarker that matters in predicting CVD is insulin resistance, which is the main factor in type 2 diabetes. A major proponent of the theory is clinical pathologist Joseph Kraft, who claims that every case of CVD started with type 2 diabetes, even if it was never identified.8

Studies show that 60–90 percent of diabetics suffer from dyslipidemia, which causes an imbalance between lipids and HDL (high-density lipoprotein) and LDL cholesterol and is also a marker for metabolic syndrome, a precursor of diabetes.

And what is a major cause of type 2 diabetes? Yes, diet—but not one that’s high in saturated fats, as the diet-heart theory maintains; it’s a diet that is high in sugars, especially the “free sugars” found in cakes, biscuits and processed food. Reducing sugar intake through a low-carb diet lowers blood pressure and insulin resistance, and in studies that have compared low-fat and low-carb diets, the low-carb diets led to “significantly greater” improvements in atherosclerosis risk.9

In another trial, some participants ate almost three times as much fat as others who had been put on a low-fat diet, and all their biomarkers for CVD fell dramatically in comparison to those eating less fat.10

The high-fat theory has been a false trail, says cardiologist Rahul Bahl. “An over-reliance in public health on saturated fat as the main dietary villain for cardiovascular disease has distracted from the risks posed by other nutrients such as carbohydrates,” he said.11

So, if you’re eating a low-carb diet, do you need to be taking statins as well? There’s no definitive evidence out there to confirm this, Diamond, Bikman and Mason say. But one major trial examining heart health—the 4S (Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study)—found that statins significantly reduced CVD risk factors only in those who had symptoms of metabolic syndrome, likely indicating they were eating a high-carb diet.12

Researchers from Nottingham University made a similar discovery. In a trial of 165,000 people, they discovered that statins were effective—that is, they reduced LDL levels to the target—in just half of the participants. Even after taking a statin for two years, these participants’ LDL levels fell minimally—again suggesting that diet had a more significant part to play.13

And if statins are targeting a fat that is actually protective, are they doing more harm than good in the long run? Several studies suggest they are. One discovered that people taking a statin were up to 2.5 times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes with complications,14 while another found that statins increased the risk of osteoporosis in people who were taking high doses of the drugs.15

When heart disease started to explode after the Second World War, doctors were desperate to understand what was happening. Ancel Keys won the argument—although it has since been discovered he cherry-picked the data to support his fats theory—and the voices of other researchers who suspected sugar as the real cause got drowned out.

Although medicine still clings to the idea that saturated fats are to blame, new research is demonstrating that sugar is the real culprit. One study, which included 110,497 people from the UK Biobank survey, discovered that “free sugars”—added sugars and those in honey, syrups and unsweetened fruit juices—doubled the risk of CVD. Other sugars, naturally occurring in fruit, vegetables and dairy, didn’t have any harmful effect.16

The fact that heart disease remains the West’s major killer despite the billions spent on statins and low-fat foods suggests medicine is getting it very wrong. A researcher from the University of New Mexico, with colleagues from Brazil and France, took another look at 35 clinical trials that had tested three types of cholesterol-lowering drugs and found that most of them showed the therapies were no better than placebo. Nearly half of the participants still went on to develop CVD and weren’t living longer.17

When Dr Robert Atkins promulgated his low-carb Atkins Diet in the 1970s, a US Senate select committee denounced his ideas as “nutritionally unsound and potentially dangerous.” Had they instead directed their ire at the processed food industry, perhaps millions of lives would have been saved.

What do you think? Start a conversation over on the... WDDTY Community