What’s in a name? A rose may smell just as sweet, but in medicine—and its drive for immediate diagnosis—the name takes on its own power and life.

Several of our friends recently had debilitating chemotherapy—and, in one case, a full mastectomy—after they had been diagnosed with breast cancer, or so they thought. While we would have counseled caution and other less aggressive approaches first, we completely understood the women had been shocked into immediate, aggressive action. The very word “cancer” can have that effect even on the best of us.

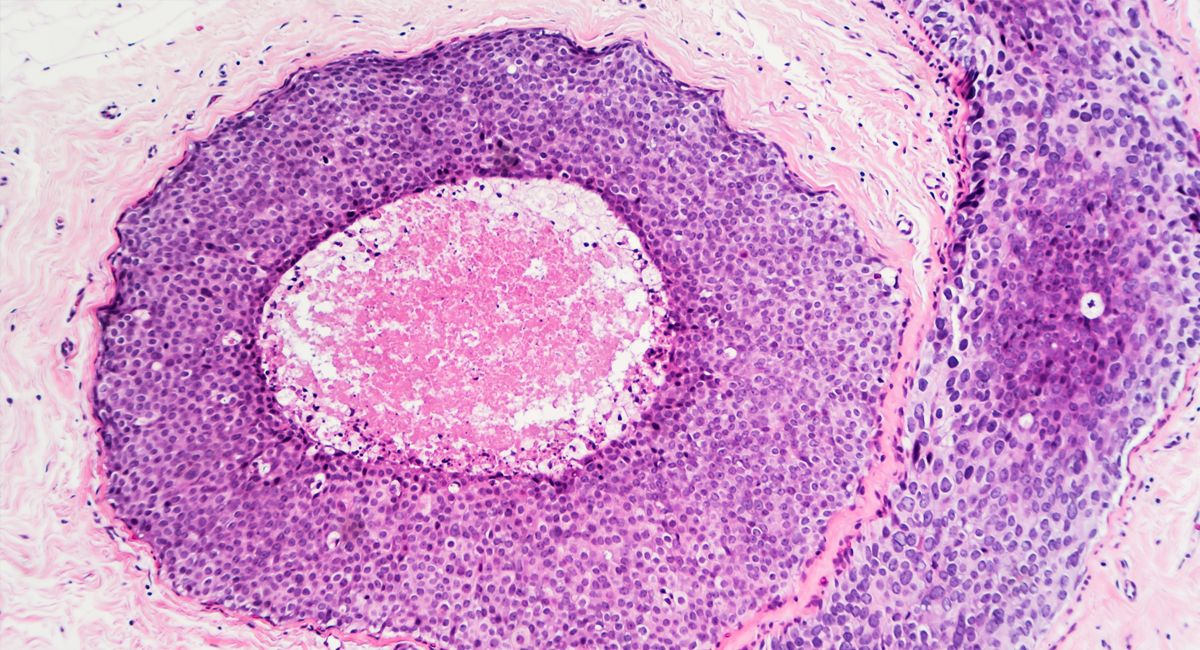

The trouble was that our friends didn’t have cancer at all. They had DCIS, or ductal carcinoma in situ. It’s also sometimes called intraductal carcinoma—there’s that dreaded word again—but it is in fact a noninvasive or pre-invasive breast cancer, often classified as “stage 0” breast cancer. Cells around the breast tissue ducts are showing some abnormalities, but there is no certainty they will spread or invade breast tissue.

In fact, 98 percent of women with a DCIS diagnosis are alive and well 10 years later, even without any treatment. Only around 1 percent of DCIS cases develop into breast cancer every year.

DCIS is a phenomenon of mass breast cancer screening. It was almost never detected before mammography, and yet today accounts for a quarter of all breast cancer “cases.”

This means that 60,000 American women and around 7,000 Britons are told each year that they have breast cancer when, in fact, they have nothing of the sort.

It could be worse. Mammography picks up only around 75 percent of DCIS cases, which means that 25 percent of screened women happily get on with their lives, unaware of any cancerous burden that medicine would otherwise place upon them.

Even in the small percentage of cases that do develop into breast cancer, the form seems to be the lowest grade and slowest growing, making it eminently treatable.

Despite all the reassurance that DCIS invariably doesn’t become cancer—and even if it does, it is one of the most benign types—women not unnaturally suffer stress and anxiety when they are given a DCIS diagnosis.

Worse, they face an arduous treatment path, with mastectomy still the preferred option. But with DCIS not even being cancer, it’s not surprising the number of health researchers who have concluded that the condition is being over-treated. This has a knock-on effect on the woman herself, of course, as the Marmot Report concluded a decade ago.1

In heralding the results of important reports like Marmot, it’s a form of lazy journalism to append adjectives like “influential,” but as its findings made not a jot of difference in the world of oncology, we should instead perhaps just say it was “vaguely interesting.”

This stubborn terrain is the home of cancer researcher Shelley Hwang from Duke Cancer Center, who for years has been trying to change the way we see, and treat, DCIS. In case oncologists weren’t keeping up with the latest research, Time magazine made their job a little easier by making Hwang one of their most influential people in 2016.

But there’s something deeper going on, suspects medical researcher Maartje van Seijen at the Netherlands Cancer Institute. Essentially, it’s about naming things. He asks, is cancer always cancer?2

Of course, cancer is always cancer, but DCIS almost never is.

This opens up a richer seam of questions. Why, for instance, are women never told what DCIS actually is—that they don’t have cancer, and possibly never will? And why do oncologists follow the most aggressive treatment protocols possible when they know the very low risk that DCIS represents?

Hwang and others have campaigned to get the “cancer” word taken out of DCIS altogether, and that would be a start. If, instead, it was called something like “minor cell abnormality”—which is what it is—a woman wouldn’t immediately stress, and perhaps it might even change the oncologist’s perception of the problem.

As to the latter, we doubt it. With DCIS taking up a quarter of the oncologist’s work—and so, as a consequence, making up 25 percent of revenues—we don’t see any change on the horizon.

That’s the power of naming things.

|

References |

|

|

1 |

Lancet, 2012; 380(9855): 1778–86 |

|

2 |

Br J Cancer, 2019; 121(4): 285–92 |