Women have been brainwashed to think that after 50, you automatically get osteoporosis. But most of what you’re told about this ‘silent’ epidemic is wrong.

If you’re a woman over 40, you’re living with the spectre of your spine slowly collapsing in on itself, with the chances of this happening to you increasing every year, if the statistics are to be believed.

According to the UK National Osteoporosis Society (NOS), one in every two British women and one in every five British men aged over 50 will fracture a bone at some point because of weak and porous bones.

In America, the statistics are more than 10 times worse: according to the US National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF), more than 40 million people currently have osteoporosis or are at high risk of developing it because of low bone mass.

And most frightening of all is the silent nature of this epidemic. Like cancer, you don’t know you have it until something catastrophic happens. You break something and if it’s your hip, it could eventually kill you.

These statistics represent an ideal scenario for the drug industry, which largely feeds off intractable illnesses that are only managed (but never cured) by a lifetime of medication-in this case, either bisphosphonates like Fosamax or hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

Although osteoporosis is indeed far more widespread than it should be, as the latest evidence demonstrates, the scale of the problem is highly inflated, largely due to changing definitions of what exactly constitutes ‘abnormal’, the limitations of sophisticated screening technology and, as always, the long arm of the drug industry.

With the help of Big Pharma-funded educational charities like the NOS in the UK and high-profile celebrities like Sally Fields, who in 2006 became the public face of Boniva, an osteoporosis drug made by Roche ,the drug industry has carried out a successful public relations campaign to instill fear in women entering middle age, encouraging them to believe that their bones will automatically collapse after menopause, a decline that can only be halted by taking a just-in-case drug.

“Everybody should be getting a bone density test,” said the actress in an interview, “because it’s the only way you can ascertain if you have osteopenia-which is the stage right before osteoporosis-or if you have osteoporosis. Your bones become so porous, like wet chalk.

“If you have osteoporosis, you need to talk to your doctor. The truth is, medicine can help, but most women with osteoporosis don’t take it long enough or they skip doses. This puts them at greater risk for breaking bones . . .”

As a good deal of scientific and anecdotal evidence demonstrates, osteoporosis is not a normal part of ageing, but a disease of our modern lifestyle.

It’s also not a life sentence. Far from being a ‘disease’ in itself, osteoporosis is, as American nutritionist and bone-health expert Dr Susan Brown argues, the outcome of the body’s desperate attempt at self-repair and biochemical rebalancing.

In many instances full-fledged osteoporosis can be halted and even reversed by making a number of simple lifestyle changes, without having to resort to a lifetime of medication, as Shelly Lefkoe did.

The entire fear campaign is based on six mistaken premises:

1 -We shouldn’t be losing much bone as we age-if we do, we have ‘pre-osteoporosis’, or ‘osteopenia’

2 -One in every two women will sustain a serious fracture

3 -Bone disease is an inevitable aspect of older age after the menopause

4 -Low bone mass equals low bone strength

5 -Bone disease occurs because of low levels of calcium

6 -Osteoporosis is irreversible.

NIX to DXA

The gold standard for bone scanning is dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, or DXA-a fancy sort of X-ray technique. You’re injected with a radioactive liquid beforehand, then asked to lie flat on a table while you’re scanned for a half-hour to an hour, or even more if a full three-dimensional view is required. Measurements are usually taken from the spine, hip, heel and forearm.

But the accuracy of this type of scan can easily be thrown off. “A walk around the room causes the measurement to change by up to 6 per cent [at the hip], which corresponds to six years of bone lost at the usual rate,” says Susan M. Ott, professor of medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle.1

Poor machine quality control and a high rate of operator error can also affect results.

The favoured technique measures many different areas at the same time-one shot of the top of the leg produces five separate measurements, for instance-but it also increases the risk of false positives.

“Apparently dramatic changes can be taken as indicating improvement or dramatic bone loss, but may simply be due to the precision of the measurement and poor repositioning technique,” wrote David M. Reid, a rheumatologist at City Hospital in Aberdeen, Scotland, and his colleagues.2

Studies show that DXA tests are not necessarily very accurate. In one study, the scans failed to detect osteonecrosis in one-sixth of confirmed cases.3

Extremes in weight (either under- or overweight), age (over 60) and even arthritis can throw off results too. In fact, the entire exercise of measuring bone mass may be useless, as bone mass doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with bone strength. Fluoride, for instance, causes bone mass to increase dramatically, but decreases its strength. This is why elderly populations in highly fluoridated communities show an increase in osteoporosis.

Myth 1: We shouldn’t be losing much bone as we age

According to the NOF in the US, nearly 22 million American women and close to 12 million men have osteopenia, a relatively new bit of medicalese (‘osteo’ = bone and ‘penia’ = low in quantity) used to describe someone whose bone density is slightly less than that of a healthy person, but not as low as someone with full-blown osteoporosis.

Bone density is usually measured with a type of scanning test called DXA (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry), which employs two beams, one high-energy and one low-energy .

T

he low-energy beam only passes through soft tissue, while the high-energy one passes through bone as well. A radiologist carrying out the test will measure a variety of bones in your body, and your bone density is then calculated by working out the difference between the two beam readings and comparing them against the ‘ideal’.

Osteoporosis is determined by the T score as a measure of bone density, which is set at zero, representing the score of an average young woman in her 20s at peak bone density. An older woman past the menopause is overwhelmingly likely to have a negative T score, and the World Health Organization (WHO) arbitrarily set the T score for osteoporosis at -2.5, or two and a half standard deviations below the ideal score. Having a bone density score between -1 and -2 standard deviations lower than that ‘ideal’ young person usually results in a diagnosis of osteopenia. To translate this into plain English, a -1 T score (1 standard deviation lower) means your bones are 10-12 per cent less dense than those of a young woman in her prime. Anything lower and you’re considered osteopenic.

According to recent evidence, measuring older people against a young standard as a measure of bone health places some 34 million women and men in the US in the category of having osteopenia.

Aside from the questionable practice of comparing bone health in middle age to bone health in your 20s, as Dr Brown points out, young people are no longer a yardstick of good health. Some 16 per cent (or one in six of all young women) also have a bone density score of -1T or lower and by that definition would also have osteopenia.

What’s more, the goalpost between osteopenia and osteoporosis keeps moving. In 2003, the US NOF redefined a T score of -2, previously the lowest level defined as ‘osteopenia’, as now representing full-blown ‘osteoporosis’. The net effect of that slight change in definition was to immediately reclassify 6.7 million American women who had been characterized as borderline healthy as having osteoporosis requiring medical treatment.

But the T score doesn’t take into account your Z score, which is your score compared with those of people your own age, gender, racial origin and weight, all of which can affect your fracture risk.

Furthermore, it’s perfectly healthy to lose bone mass as we age; the problem isn’t mass, but the ability of bone to self-repair .

Myth 2: One in every two women is at risk of fracture

This vastly overblown figure mostly comprises the ‘silent’ vertebral fractures that don’t cause pain and mostly heal on their own. The true lifetime incidence of hip fractures is 17 to 22 per cent for 50-year-old women, and 6 to 11 per cent in men.1 Even the US Surgeon General estimates that only 17 per cent of women (about one in six) aged over 50 will fracture a hip, while the average age for such a fracture is 82.

Also, most of these hip fractures occur from a fall, and when the women sustaining falls are examined and compared with healthy controls, there is a considerable similarity between the two groups in bone mineral density and bone mass, suggesting that other factors are responsible, such as physical inactivity, loss of muscle strength, impaired cognition or vision, chronic illness, and the use of one or more of a number of prescription drugs.2

And calamitous though a hip fracture may be at advanced ages, it may not be fatal. Although one-fifth of all elderly patients die within a year of a hip fracture, it’s not clear whether their death was due to the fracture or to general frailty.3

Myth 3: Bone disease is an inevitable aspect of older age after the menopause

It’s true that we lose bone mass as we age, just as we lose muscle mass; according to Dr Brown, we reach our peak of bone mass at about age 30 to 35, after which we lose about 25 per cent of bone between then and age 80. However, even ageing bone should be healthy and capable of ongoing self-repair .

One study of the remains of Caucasian women living between 1729 and 1852, and buried beneath a London church-many of them postmenopausal at the time of death-showed that their bones were stronger and denser than those of most modern-day women, whether old or young, and the rate of bone loss in the hip was significantly lower.4 And American dentist Weston Price, who travelled around the world in the early 1930s studying the health and diet of traditional societies, concluded that many traditional populations enjoyed excellent bone health throughout their lives.5

Modern evidence also shows a sharp rise in the incidence of hip fractures in the latter part of the 20th century. Studies of women in Nottingham found that the incidence had doubled between 1971 and 1981, as they did in Sweden over roughly the same time period.6 This suggests that there’s something about the changes we’ve made in our modern lifestyles in the latter quarter of the 20th century that’s killing our bones.

But not all populations of women around the world have a high incidence of osteoporosis. Mayan women in Mexico and Guatemala have virtually no osteoporosis even though they live to an average age of 80.7 Even in the US, certain ethnic groups, such as African Americans, have half the incidence of Caucasian women in the US,8 and Yugoslavia, Singapore and Hong Kong have extremely low rates of bone fracture due to osteoporosis. In Japan, vertebral fractures among postmenopausal women are virtually non-existent, and hip fractures among elderly Japanese are less than half those of their Western counterparts.9

The evidence is clear that this is not just a disease of middle-aged women or of people aged over 50. An estimated 30 per cent of men will have a fracture related to osteoporosis in their lifetimes. Also, fractures of the forearm, the most common breaks in children, have increased by 32 per cent in boys and 56 per cent in girls over the past 30 years, especially among the overweight.10

All of this suggests that osteoporosis isn’t an inevitable part of growing old or the time after menopause, but instead has something to do with our contemporary lifestyles.

Myth 4: Low bone mass equals low bone strength

Measuring bone mass may be a red herring and a meaningless measure of true fracture risk. A recent study found that about half of patients who’d sustained fractures had bone mineral density scores above the diagnostic T score of -2.5, which should have meant their bones were supposedly not at risk.11

Such studies suggest th

at the rate of bone turnover (that is, bone ‘resorption’ in medicalese) and very low levels of hormones such as estradiol and DHEA may be a better indicator of true fracture risk than bone mineral density. In one study following nearly 150,000 postmenopausal women for a year after having a DXA scan, those at high risk because of risk factors had only 18 per cent of the osteoporotic fractures observed, indicating that 82 per cent of those with good T scores and supposedly good bones had a fracture that same year.12

Myth 5: Osteoporosis is linked to low levels of oestrogen and calcium

It is true that oestrogen does mediate bone mineralization and that higher levels of oestrogen protect against bone loss earlier in life, but this argument assumes that Nature made a terrible mistake when designing human female physiology and that women should have been equipped with high levels of oestrogen and other hormones their entire lives.

But osteoporosis is not universal, and in developing countries like Surinam in South America, the incidence of osteoporosis among the elderly is far lower than in a similar US population, even though native South Americans consume far less calcium in their diet and presumably go through menopause without hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Also, countries with the highest intakes of calcium have been shown to have the highest rates of hip fracture.13

The evidence suggests that it’s more to do with how your body processes a number of nutrients and that osteoporosis isn’t an isolated health issue, but linked to many other predisposing disease factors. In one study of elderly women, for instance, osteoporosis was linked to overall nutrition and the ability of the body to store fat and protein. Women with osteoporosis had a tendency towards greater risk of malnutrition, had poorer appetites and more often suffered from cardiovascular diseases, said the researchers.14

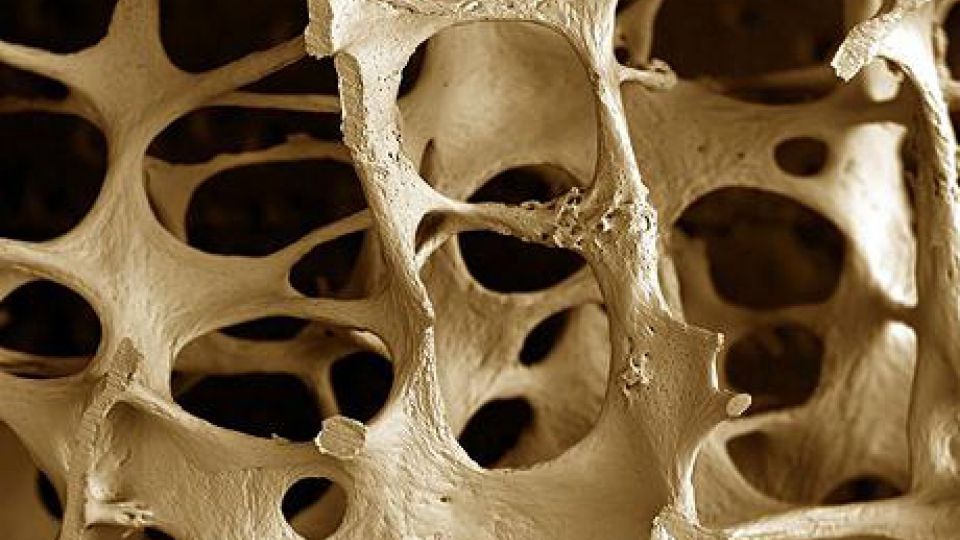

Lifelong redecorating

Bone in healthy individuals is a dynamic living entity constantly undergoing interior remodelling. Two sets of cells are responsible: osteoclasts-the construction workers-which rip down worn-out bone; and osteoblasts-the architects-which use calcium, magnesium, boron and other minerals to build up healthy new tissue. This process is called ‘resorption’ and, over several weeks, it repairs the tiny microfractures that occur every day due to normal stresses. We also have the ability to rebuild lost bone mass, and even those who’ve suffered malnutrition or a severe illness can rebuild bone mass once a healthy nutritional status has been restored-even well into our eighth decade of life.1

Bones break because they have lost the ability to repair those everyday microfractures occurring because of normal movement. The problem isn’t one of density or thin bones, but a diminished capacity to remodel and self-repair largely because of a lack of the right nutrients and physical activity, chemical overload from pollutants in the environment and even prescription drugs.

Bone is also the central repository of the body’s mineral stores, and when your circulating blood is low in a variety of nutrients like calcium, magnesium and phosphorus, the body draws from this storehouse, as it does when it needs certain buffering compounds to restore too high levels of acid in the body to the optimal acid-alkaline balance.

Ordinarily, this short-term emergency nutrient loss is replenished by minerals from a healthy diet; if it isn’t, then the bone is depleted and osteoporosis is the result. Seen in this light, says Dr Susan Brown, “osteoporosis is really the end-product ‘disorder’ of our body’s lifelong attempt to maintain a crucial internal ‘order’.”

Myth 6: Once bone is lost, it’s lost forever

Bone has the ability to repair itself at all times in life, even when hormone levels are not high (unless you take bisphosphonate drugs, which virtually stop all rebuilding of bone). One study examining the bones of a group of women aged between 30 and 85 found a significant difference between the bones of women who were very active and those who were not-no matter what their age.15 Another study of female patients in a nursing home with an average age of 81 showed they were able to increase their bone mineral density by doing physical exercise and supplementing with calcium and vitamin D for three years.16 A French study of more than 3,000 healthy women with an average age of 84 showed that those taking 1.2 g of elemental calcium plus 800 IU of vitamin D3 had 42 per cent fewer hip fractures than the control group given a placebo after just 18 months. Femoral (thigh) bone density in the treated group rose by 2.7 per cent, whereas it fell by 4.6 per cent in the placebo group.17 By making a few lifestyle changes, it’s never too late to rebuild your bones.

The fall guys

When elderly women break a hip, it’s automatically blamed on weak bones, and not on the increased likelihood of a fall. Any of the drug categories below can increase your likelihood of suffering a

bone-fracturing fall:

tranquillizers

barbiturates

painkillers

antihypertensives

anticonvulsants

sedatives

antidepressants

Not the biz

“I feel it’s kind of a miracle,” said Sally Fields about her drug for which she had a daily blog on her site Rally with Sally. “This month, the whole family is taking a trip together to Hawaii… I’ll be packing for fun, which means plenty of exercise to keep my bones strong. And I won’t have to pack a load of medication since just one Boniva(R) (ibandronate sodium) tablet will help protect my bones for the entire month.”

Drugs like Boniva, Fosamax, Reclast and Actonel have all become international best-sellers primarily among postmenopausal women, the group that suffers most from osteoporosis, and even more so since HRT’s dramatic fall from grace. These drugs make use of a chemical that is claimed to mimic bone-building compounds found naturally in the body. Yet, all that the usual drugs for osteoporosis like oestrogen, calcitonin and etidronate (called ‘antiresorbing drugs’) do is lower the processes of bone turnover and renewal, preventing the hard-hat osteoclasts (see box, page 29) from doing their job.

As Dr Susan Ott says, “Bone biopsies from patients taking bisphosphonates show 95 per cent reduction in the bone formation rate. The bisphosphonates get deposited in the bone and will accumulate for years. It is possible that many years of continuous medicine would make bone more brittle or impair the ability to repair damage. After five years, the fracture rates are as high in the women who keep taking alendronate [Fosamax] as in the women who quit.

“

And that’s what doctors are now discovering. Two studies have found that bisphosphonates increase the risk of ‘atypical’ fractures-like fractures in the femur (thigh bone), which extends from the hip to the knee, and subtrochanteric fractures, or those in the femur below the hip joint.

Researchers reckon that women who take bisphosphonates regularly for five years or longer increase the risk of atypical fractures by 2.7 times compared with those who take the drug only occasionally or for less than 100 days.1

Another study showed that the drugs cause ‘fatigue fractures’, and the risk disappears within a year of stopping the medication. In one study of 12,777 women aged 55 years and older, 59 suffered a ‘fatigue fracture’, and 46 of them were taking a bisphosphonate at the time.2

It’s also now known that users of this drug risk developing osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), or ‘dead jaw syndrome’. In this scenario, bone tissue fails to heal after a routine tooth extraction, so leading to bone infection and fracture or surgery to remove the dead bone, as seen in cancer patients given the drug.3

As Dr Susan Ott puts it: “Many people believe that these drugs are ‘bone-builders’, but the evidence shows they are actually bone-hardeners.”

And that’s in addition to all the other side-effects like atrial fibrillation, hypertension, anorexia, bone and joint pain, and anaemia-all of which predispose you to… osteoporosis.

Lynne McTaggart

|

1 |

Butler M et al. Treatment of Common Hip Fractures. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2009; online at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK32595/ |

|

2 |

Ageing Res Rev, 2003; 2: 57-93; Drugs Aging, 2005; 22: 877-85 |

|

3 |

J Am Geriatr Soc, 2006; 54: 1885-91 |

|

4 |

Lancet, 1993; 341: 673-5 |

|

5 |

Price WA. Nutrition and Physical Degeneration (new edn). New Canaan, CT: Keats Publishing, 1997 |

|

6 |

Lancet, 1983; 1: 1413-4; Acta Orthop Scand, 1984; 55: 290-2 |

|

7 |

Love S. Dr. Susan Love’s Hormone Book. New York: Random House, 1997 |

|

8 |

Osteoporos Int, 2011; 22: 1377-88 |

|

9 |

Proc Soc Exp Biol Med, 1992; 200: 149-152 |

|

10 |

Nutr Today, 2006; 41: 171-7 |

|

11 |

J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact, 2004; 4: 50-63 |

|

12 |

Arch Intern Med, 2004; 164: 1108-12 |

|

13 |

J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2000; 55: M585-92 |

|

14 |

Medicina [Kaunas], 2006; 42: 836-42 |

|

15 |

Med Sci Sports Exerc, 1986; 18: 576-80 |

|

16 |

Med Sci Sports Exerc, 1981; 13: 60-4 |

|

17 |

N Engl J Med, 1992; 327: 1637-42 |

|

nix to dxa References |

|

|

1 |

BMJ, 1994; 308: 931-2 |

|

2 |

BMJ, 1994; 308: 1567 |

|

3 |

Presentation at the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, February 1999, Anaheim, California |

|

4 |

BMJ, 1996; 312: 296-7 |

|

lifelong redecorating References |

|

|

1 |

Med Sci Sports Exerc, 1981; 13: 60-4 |

|

not the biz References |

|

|

1 |

JAMA, 2011; 305: 783-9 |

|

2 |

N Engl J Med, 2011; 364: 1728-37 |

|

3 |

J Natl Cancer Inst, 2007; 99: 1016-24 |

What do you think? Start a conversation over on the... WDDTY Community