Lymphatic drainage is the key to beating ME/CFS, says Dr Raymond Perrin

Treating a patient for back pain in 1989 led osteopath and neuroscientist Raymond N. Perrin to the concept that there was a structural basis to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). He has since spent three decades sifting through the scientific evidence on the condition and developing an effective technique based on lymphatic drainage—The Perrin Technique—for treating sufferers.

Here are his central findings.

Fact 1: Fluid flow

Fluid flows around the brain and continues up and down the spinal cord. This is known as cerebrospinal fluid and has many functions, including being a protective buffer to the central nervous system and supplying nutrients to the brain. But one function that has received significant scientific attention only recently is the role it plays in the drainage of large molecules, including many poisons (toxins), out of the central nervous system into the lymphatic system.

This system, which I have referred to since 1989 as “neuro-lymphatic drainage,” has now been proven to exist by a brilliant group of scientists in the US and Europe who have termed this drainage “the glymphatic system,” as it has been shown to drain toxins from support cells in the brain known as the ‘glia’ to the lymphatics.1 In fact, actual lymphatic vessels have been discovered in the membranes of the brain in both animal and human studies, which can now be visualized by MRI scanning.2

Fact 2: Getting the toxins out

The lymphatic system is an organization of tubes around the body that provides a drainage system secondary to the blood flow. Why does the body need a secondary system to cope with poisons or foreign bodies in the tissues? Are the veins not good enough? The answer is size.

The blood processes poisons and particles that enter the circulatory system via the walls of microscopic blood vessels known as capillaries. Their walls resemble a fine mesh which acts as a filter, allowing only small molecules to enter the bloodstream itself.

When the blood reaches the liver, detoxification takes place, cleansing the blood of its impurities. Larger molecules of toxins often need breaking down before entering the blood circulation, and they begin this process of detoxification in the lymph nodes on the way to drainage points just below the collar bone into two large veins (the subclavian veins). Most of the body’s lymph drains into the left subclavian vein.

The capillary beds of lymphatic vessels, known as terminal or initial lymphatics, take in any size of molecule via a wall that resembles the gill of a fish, opening as wide as is necessary to engulf it. The lymphatics also help to dispose of some toxins and impurities through the skin (via perspiration), urine, bowel movements and breath.

Once toxins have drained into the subclavian veins, they eventually find their way into the liver where they are broken down.3

Fact 3: The pumping mechanism

Initially, the lymphatic system was thought not to have a pump of its own. Its flow was believed to depend on the massaging effect of the surrounding muscles and the blood vessels lying next to the lymphatics, akin to squeezing toothpaste up the tube.

But we now know that the collecting vessels and ducts of the lymphatic system have smooth muscle walls,4 and that the main drainage of the lymphatics, the thoracic duct, has a major pumping mechanism in its walls.5 This is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system.6

If there is a disturbance of the sympathetic nervous system, the thoracic duct pumping mechanism may push the lymph fluid in the wrong direction and lead to a further buildup of toxins in the body.

Fact 4: The sympathetic nervous system

The sympathetic nervous system is part of the autonomic nervous system of the body, which deals with all the automatic functions of the body. Although it’s known for being the system that helps us in times of danger and stress, often referred to as the ‘fight or flight’ system, the sympathetic nervous system is also important in controlling blood flow and the normal functioning of all the organs of the body, such as the heart, kidneys and bowel. And it’s vital for healthy lymphatic drainage.

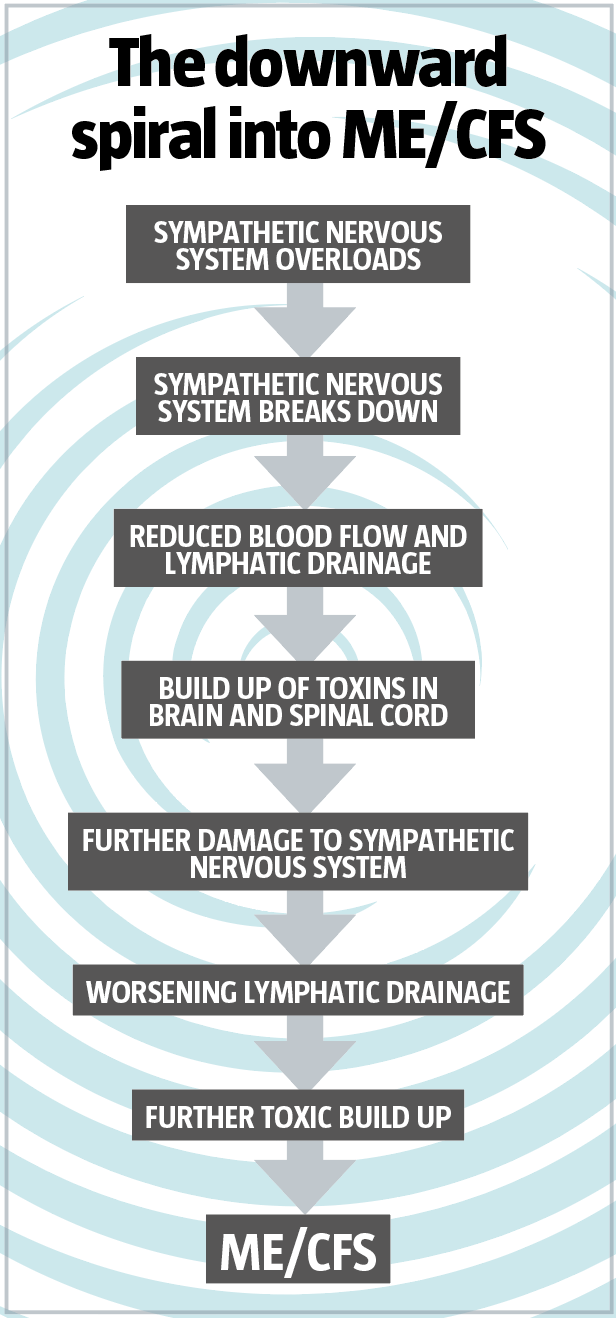

In ME/ CFS and fibromyalgia sufferers, the sympathetic nervous system will have been placed under stress for many years before the onset of the signs and symptoms. This stress may be of a physical nature due to postural strain or an old injury, or it may be emotional, environmental (such as pollution) or due to stress on the immune system due to infection or allergy.

The sympathetic nerves spread out from the thoracic spine to all parts of the body. The hypothalamus, a part of the brain just above the brain stem, acts as an integrator for autonomic functions, receiving regulatory input from other brain regions, especially the limbic system, which involves emotion, motivation, learning and memory. The hypothalamus also controls all the hormones of the body.

Fact 5: Biofeedback

The hypothalamus controls hormones by a process called biofeedback. This mechanism can be explained with the following example. If the sugar levels in the body are too low, it may be due to a rise in the hormone insulin, which is produced in the pancreas. Insulin, like other hormones, is a large protein molecule that travels through the blood and stimulates the breakdown of sugar. It passes from the blood into the hypothalamus, which will calculate if more or less insulin production is required and, accordingly, send a message to the pancreas to make the necessary adjustments.

The region of the hypothalamus is one of a few areas of the brain that allow the transfer of large molecules into the brain from the blood (known as circumventricular organs). In all other parts of the brain there is a filter known as the blood–brain barrier (BBB) that separates the blood from the cerebrospinal fluid. The BBB contains tight junctions that prevent toxins and other harmful material entering the brain’s cells from the blood. However, protein transport molecules that can cross the BBB can carry these huge protein molecules, enabling the biofeedback mechanism to work and allowing the transfer of hormones into the brain.

Water molecules are small enough to naturally pass through the BBB via channels within membrane proteins known as aquaporin. Due to the tight junctions in the BBB, the transport of larger molecules is limited through the cells that line the blood vessels separating the blood and the brain’s tissue.

Evidence suggests that these barriers are subject to damage from neurotoxic chemicals circulating in blood. The aging process and some disease states also render barriers more vulnerable to damage.

In many disease states, gaps in the BBB plus dysfunctional protein transporters mean that large toxic molecules can invade the brain and wreak havoc on the normal functioning of the central nervous system.7 In ME/CFS, it’s been proven that many immune cells that are pro-inflammatory do just this.8

Fact 6: What goes wrong

The central nervous system, composed of the brain and the spinal cord, is the only region in the body that for hundreds of years was believed to have no true lymphatic system. Since the lymphatics exist to drain large molecules, what can the central nervous system do if attacked by large toxins?

It’s now been demonstrated that the cerebrospinal fluid drains toxins along minute gaps next to blood vessels, called paravascular spaces, and these transport the toxins into fluid in spaces within the arterial walls, known as perivascular spaces, and then onto the lymphatic system outside the head through perforations in the skull.

Drainage also occurs from the perivascular pathways into lymphatic vessels in the outer layer of the meninges, the membranes surrounding the brain.2 The lymphatic vessels in the head and around the spine take toxins away via the thoracic duct and right lymphatic duct into the blood and the liver where they are broken down.9

This drainage mechanism has now been filmed, with the largest amount draining through a bony plate situated above the nose (known as the cribriform plate).10 The toxins then drain into lymphatic vessels in the tissue around the nasal sinuses. There is further drainage down similar channels next to blood vessels supplying the cranial nerves, especially the optic, auditory and trigeminal nerves in the eye, ear and cheek respectively, and also down the spinal cord outward to pockets of lymphatic vessels running alongside the spine.11

Fact 7: Build-up of toxins

In ME/CFS, I believe it is these drainage pathways, both in the head and spine, that are not working sufficiently, leading to a build-up of toxins within the central nervous system.

The reasons for drainage problems can vary from patient to patient. It may be trauma to the head from an accident; it may be hereditary or due to a problem at birth. The spine may become out of alignment—especially in very active teenagers—which can lead to a disturbance in normal drainage. If the spine and brain are both affected, the increased toxicity will disturb hypothalamic function and will therefore further affect sympathetic control of the central lymphatic vessels. This in turn pumps more toxins back into the tissues and brain via the perivascular and paravascular spaces, which further affects hypothalamic and sympathetic control. With this, a vicious circle has started.12

ME/CFS is very much a biomechanical disorder with clear and diagnosable physical signs, including disturbed spinal posture, enlarged lymph vessels and specific tender points related to sympathetic nerve disturbance and backflow of lymphatic fluid. Fluid drainage from the brain to the lymphatics moves in a rhythm that can be palpated using cranial osteopathic techniques. A trained practitioner can feel a disturbance of the cranial rhythm in ME/CFS sufferers.13

The Perrin Technique helps drain the toxins away from the central nervous system and incorporates manual techniques that stimulate the healthy flow of lymphatic and cerebrospinal fluid and improve spinal mechanics. This in turn reduces the toxic overload to the central nervous system, which subsequently reduces the strain on the sympathetic nervous system and ultimately aids a return to good health.

One of the key treatments I use for patients with ME/CFS is effleurage, a method of massage that requires stroking motions along the surface of the head, neck and trunk. The exact nature, content, intensity and timing of each treatment is determined by a trained and experienced practitioner, but the general goal is to relieve congested lymphatics throughout the body.

To avoid any friction, which will aggravate any inflammatory condition, it’s important to use plenty of lubrication when carrying out effleurage, and the right type of oil or cream. I like to use coconut oil and sweet almond oil, but other natural, hypo-allergenic and unscented oils or creams will work too. Don’t use baby oil as it is a perfumed mineral oil, a byproduct of refining crude oil to make gasoline and other petroleum products. It’s composed mainly of alkanes and cycloalkanes which, like other hydrocarbons benzene and formaldehyde, can cause damage to the nervous system.

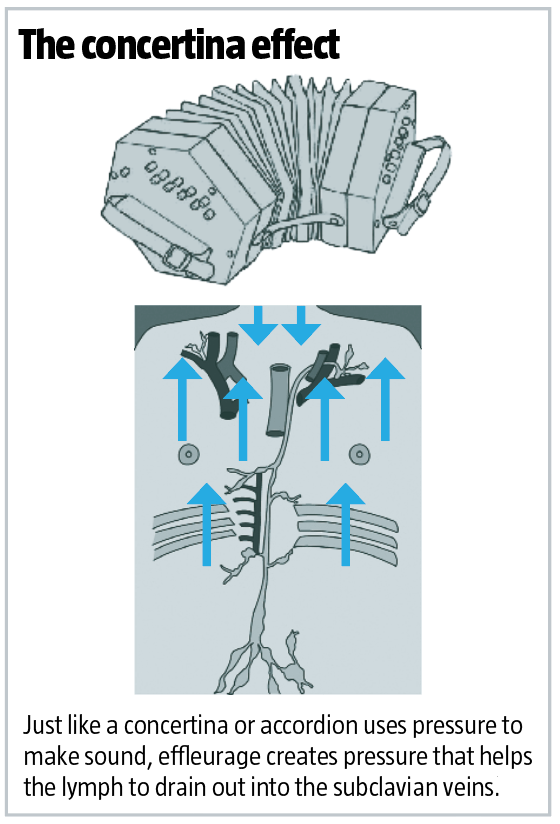

The gentle strokes are carried out rhythmically toward the subclavian region, which creates what I call the “concertina effect.” As with a concertina or accordion, where putting pressure on the ends of the bellows forces air through the instrument to produce the desired musical effect, so effleurage performed toward either clavicle (collarbone) on both sides creates a pressure that forces the lymph to drain out through the central drainage into the subclavian veins (see image opposite).

This increased pressure of lymphatic fluid produced within the thoracic and right lymphatic ducts creates a negative pressure in the lymphatic vessels above and below, which then produces what is known as the siphon effect, which will be familiar to anyone who has ever cleaned out a fish tank—sucking on a tube creates a pressure gradient. Fluid will always flow from an area under higher pressure to an area of lower pressure. So, lymph will continue to drain from the entire system, eventually including the lymphatic system of the brain and spinal cord. Toxins stuck in the central nervous system, some for many years, will slowly and surely drain away after being sucked up, just like the siphon tube in the fish tank, into the main trunks and ducts of the lymphatic system.

I developed ME after a nasty bout of glandular fever [Epstein–Barr virus, also called mononucleosis] at age six. I was eventually diagnosed at 11 years old, and my condition got progressively worse over the next seven years.

By the time I reached my eighteenth birthday, I was extremely unwell. I was wheelchair-bound, unable to stand for more than a few seconds, light sensitive, noise sensitive, very nauseous and in constant severe pain and fatigue.

After so many years of being severely ill my body was giving up, and at 18, so was I. I had to rely on my parents as carers, couldn’t leave the house and had no quality of life.

My mum did some research

on the Perrin Technique and agreed it was worth a try. Until this point no other treatment had helped me, including seven years under a pediatric consultant, a referral to the head of pediatric ME for the country, graded exercise, pacing, allergy testing, diets and several alternative therapies.

We met with Dr Perrin and the treatment made immediate sense to us. He explained ME in a way nobody else ever had. All the symptoms that other doctors had brushed off suddenly had a real medical explanation, and thankfully, an answer.

I was examined by Dr Perrin and graded at 2/10 on the Perrin scale, which is severe, but I was still able to be helped. As expected, I got worse before I got better on the program.

After one particular treatment, I reacted severely and was partially paralyzed for 24 hours. This reaction, although rare and frightening at the time, was the best thing that could have happened to me as once I got through it, my recovery accelerated and I was soon seeing vast improvements in my condition.

I took my first steps shortly after this reaction and dumped the wheelchair for good a mere four and a half months after starting my Perrin journey. By September, I was working part-time, had enrolled in college and was practicing for my driving test, which I passed the next month. I was starting to finally lead a normal life for the first time in 11 years.

A year after I ditched the wheelchair, I challenged myself and did a sponsored climb up Scafell Pike, the tallest peak in England. On reaching the top and looking out over the Lake District I knew I was never going back to being that ill shell of a person thanks to Dr Perrin and the Perrin Technique.

Nine years on and, although I still have treatment every couple of months to ensure I stay well, I am largely symptom-free. Without the treatment, there’s no way I would have the life I have today, and I am forever grateful for the second chance at life that it gave me.

Another technique is gentle articulation of the thoracic and upper lumbar spine, plus stretching and articulation of the ribs along with effleurage of the lymphatics that run up either side of the spine. This combination of gentle articulation and soft tissue techniques improves movement of the thoracic and upper lumbar spine and the ribs and relaxes the muscles around the spine.

This is achieved together with upward effleurage from the waist to the level of the collarbone to increase the lymphatic drainage of the spine.

The main objective of the articulatory, soft tissue techniques and occasional high-velocity manipulation is to improve the structure and overall quality of movement of the dorsal and upper lumbar spine. All the articulatory techniques are slowly and gently applied with minimal force in order to avoid irritating spinal inflammation and reduce any reactive spasm from the surrounding muscles.

Improving the biomechanics of the spine and lymphatic flow in this region aids overall neuro-lymphatic drainage. This is all helped by the very rhythmic and gentle nature of this technique, which, when combined together with stretching and movement of the ribs, creates an extremely relaxing yet powerful treatment, not just for ME/CFS but also for many upper body mechanical dysfunctions and general upper back pain.

This technique will also help relax the diaphragm—the muscle wall between the abdomen and thorax. Helping reduce diaphragmatic tension will aid lymphatic drainage.

After increasing the movement of the restricted spine and relaxing the surrounding muscles, it’s important to try to improve respiratory mechanics. This is crucial in ME/CFS patients, since the amount of oxygen in the body affects the chemical content of the body, and this has a direct effect on the body’s tissues.

Reduced oxygen produces greater fatigue in the patient and will aggravate symptoms. By improving the mechanics of respiration in the rib cage, the patient’s lung capacity is increased when they inhale, thus raising their oxygen intake.

Inhalation has been shown to aid cerebrospinal fluid motion, which in turn aids the cranial rhythmic impulse (CRI), which I believe drives neuro-lymphatic drainage.14

The most important and powerful part of the treatment is stimulation of the cranio-sacral rhythm by cranial and sacral techniques, which occurs toward the end of a consultation. This directly affects the fluctuating CRI.

Cranial techniques, which involve gentle pressure and minimal movements, have been shown to be effective in helping all aspects of health. Similar to the effects of the thoracic duct pump on the entire lymphatic system, the CRI can, by skilled practitioners, be palpated throughout the body as the lymph spreads throughout the organs and limbs.14

The direction of force through the hands and arms of the practitioner when applying this technique resembles the mechanism of pumping and sucking the air in and out of a blacksmith’s bellows, but with far less pressure. During the compression phase of this gentle technique, the volume within the ventricular system is reduced, forcing the cerebrospinal fluid out and thus drainage through the various pathways.

Immediately after treatment the patient may feel slightly giddy and possibly even nauseous. This is due to the fact that nasty toxins are being released from the central nervous system during the half hour or so of the treatment session. To help with this, I recommend a few choice supplements, such as vitamin C, garlic and grapefruit seed extract.

With the Perrin Technique, less is more, particularly in the early stages of treatment. Care should be taken not to overstimulate the drainage, especially the cranial rhythm, with too long or forceful a treatment as it may cause too much of a severe reaction.

As the therapeutic program progresses and the patient improves, the treatment can gradually be increased.

In addition to treatment from a trained practitioner, there are a number of self-help exercises that can help with lymphatic drainage. Try the following in sequence; just make sure you don’t do anything that causes pain.

Upper thoracic rotation exercise

This gentle rotation is designed not to stretch muscles and joints, but gradually and subtly to increase movement of the upper back. The movement should be as rhythmic and relaxed as possible.

•Sitting down, facing ahead, place your hands around both sides of your neck with thumbs nearest your shoulders, elbows facing forward and down.

•Slowly rotate the upper body first to the right (from the waist up) keeping your head and neck facing the same direction as your upper body. Only rotate or twist about 45° in total.

•Now twist gently and slowly, without stopping in the middle, to the left side.

•Repeat five times each way.

Mid-thoracic rotation exercise

This exercise encourages movement in the middle section of the thoracic spine.

•Repeat the same rotation as above, but this time cross your arms and hug your shoulders with your hands.

•Repeat the movement five times each way, making sure that your head, neck and shoulders all stay in line.

Lower thoracic rotation exercise

This exercise improves mobility of the lower thoracic spine.

•Repeat the same movement, but with your arms folded at the waist.

•Repeat the movement five times each way, again keeping your head, neck and shoulders in line.

Shoulder rolling exercise

Finish these exercises with some shoulder rolls:

•Standing up if you are able, gently roll your shoulders slowly forward five times and then slowly backward five times.

Adapted from The Perrin Technique by Dr Raymond Perrin(Hammersmith Health Books, 2019).

To find a practitioner trained in the Perrin Technique, visit www.theperrintechnique.com

|

References |

|

|

1 |

J Psychosom Res, 1995; 39: 633–40; J Psychosom Res, 2002; 52: 485–93; Ann Behav Med, 2002; 24: 106–12; J Psychosom Res, 2003; 54: 439–43. |

|

2 |

J Intern Med, 2011; 270: 327–38 |

|

3 |

Beyond myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: redefining an illness. Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2014. |

|

4 |

Front Pediatr, 2018; 6: 242 |

|

5 |

J Chronic Fatigue Syndr, 2007; 14: 77–85; J Intern Med, 2010; 268: 265–78; Psychol Med, 2003; 33: 197–201 |

|

6 |

Popul Health Metr, 2004; 2: 1 |

|

7 |

Lancet, 1961; 1: 1371–4; Med J Aust, 1995; 163: 294–7; Ann Occup Hyg, 2003; 47: 261–7; Tired or Toxic. Syracuse, New York: Prestige Publishing; 1990; Psychosom Med, 1996; 58: 38–49; Arch Int Med, 1994; 154: 2049–2053; Psychiatry Res, 2000; 95: 67–74 |

|

8 |

Aust N Z J Psychiatry, 1992; 26: 249–56 |

|

9 |

J Clin Pathol, 2007; 60(2): 113–6 |

|

10 |

Biomedicines, 2017; 5: 15; J R Soc Med, 1991; 84: 118–21; Am J Med Sci, 1871; 61: 17–52 |

|

11 |

Nature, 1997; 386: 721–4; Neuroreport, 2003; 14: 225–8; Med Hypotheses, 2003; 60: 840–2 |

|

12 |

NZ Med J, 1989; 102: 126–7; CFIDS Chronicle, 1995; 55–8 |

|

13 |

Int J Clin Pract, 2004; 58: 297–9; Cur Cardiol Rep, 2010; 12: 503–8 |

|

14 |

J Neurosci, 2015; 35: 2485–91 |