Mary Ellen Williams looked at the doctor in shock when he told her the bad news: her husband Harold was losing his memory. In one test he had been given, Harold had only been able to recall three of 30 words.

“The doctor looked at me as if to say, ‘How did you miss that he had such bad memory problems?'” Mary Ellen recalls. It wasn’t as if she had overlooked her husband’s trouble altogether, however; that’s why they were at the doctor’s office after all.

Harold first began to notice he was having difficulty remembering things at about age 52. He would forget things he meant to pick up at the store or where he put things. He began writing lists, which he hadn’t done previously, but soon realized he was even forgetting listed items.

“I would get home and realize I hadn’t stopped somewhere,” he says. It sounds like trivial things, he adds, but they added up to something noticeable. His work in mechanical maintenance for high-end communications equipment was affected, and it was worrying.

Mary Ellen noticed changes in Harold too. “He started to repeat the same stories. Or he would point out something as we were driving by that he had pointed out just a few days earlier.”

Neither had realized quite how bad the situation was until his test scores came in and the doctor said Harold had cognitive impairment. It was a frightening diagnosis. Harold and Mary Ellen both saw it as something that leads slowly but inevitably in a one-way direction to dementia such as Alzheimer’s disease.

The real pandemic

Alzheimer’s is the number one pandemic of the elderly in the twenty-first century. In the US alone, an estimated 5.6 million people age 65 and older – about one in 10 older Americans – were living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia in 2019. In addition, an estimated 18.8 percent of Americans in this age group have cognitive impairment, about a third of whom may develop dementia within five years.1

The statistics are equally grim across developed nations. In 2019, there were over 850,000 people with dementia in the United Kingdom, for example, which equates to about one in every 14 Brits over 65 who have lost their mental capacities.2

“Worldwide, at least 44 million people are living with dementia, making the disease a global health crisis that must be addressed,” states the Australian Alzheimer’s Association.3

In 2017, Alzheimer’s-related dementia was the third leading cause of death in the US, after heart disease and cancer, and researchers from the Boston University School of Public Health think the official numbers may actually underestimate the true picture of Alzheimer’s mortality.

Using information from the medical records and death certificates of 7,342 adults between the ages of 70 and 99 to estimate the percentage of deaths attributable to dementia in the US between 2000 and 2009, the researchers estimate that 13.6 percent of all deaths are due to dementia – a figure 2.7 times higher than the official statistics.

Adding in estimates for deaths from cognitive impairment without dementia, the researchers conclude that “the overall burden of cognitive impairment on mortality was an estimated 23.8 percent, which is 4.8 times the underlying cause of death estimate.” That’s nearly one in four deaths linked to dementia.1

If the numbers on Alzheimer’s are scary, the lack of mainstream treatment options makes a diagnosis even more devastating. Almost any official health website will say something along the same lines as the US Department of Health and Human Service’s National Institute on Aging, which defines Alzheimer’s as “an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, and, eventually, the ability to carry out the simplest tasks.”4

Despite billions spent developing hundreds of potential new drug treatments, all these new pharmaceuticals have failed to slow – let alone show any ability to reverse – Alzheimer’s dementia or cognitive decline.

A handful of drugs might be prescribed to temporarily stave off memory loss for a few more months of day-to-day functioning, but as the prestigious Mayo Clinic explains, “Unfortunately, Alzheimer’s drugs don’t work for everyone, and they can’t cure the disease or stop its progression. Over time, their effects wear off.”

Repairing the brain

However, in the last decade, research has exploded in the field of non-drug interventions – lifestyle changes including diet and exercise, friendships and even prayer – for cognitive decline and neurological conditions including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Evidence is mounting that our brains are more adaptable than we’ve thought, and that we can repair damage and halt and even reverse cognitive decline by changing our habits.

Psychiatrist Daniel Amen has been a forerunner in the field of reversing brain decline. In 2011, he published a study of 30 retired professional football players who had demonstrated brain damage and cognitive decline from decades of repeated head injuries or substance abuse. (Amen was the medical consultant on the 2015 film Concussion, based on the true story of the doctor who discovered brain disease in American football players as a result of repeated head injuries).

When the former athletes were encouraged to lose weight and take nutritional supplements (see box, right) more than half of them experienced significant improvement in brain function and cognitive performance, and their brains showed an ability to regrow or reorganize neural networks – a phenomenon known as neuroplasticity.5

Imaging the brain

In addition to cognitive testing, Amen used SPECT scans – single photon emission computed tomography – to demonstrate the players’ improvement. SPECT uses a radioactive tracer to detect blood flow in tissues and organs, including the brain. The radiation exposure is roughly equivalent to a standard CT scan of the head.

“SPECT basically shows three important things about each area of the brain: if it is healthy, underactive or overactive,” Amen writes in his latest book, The End of Mental Illness (Tyndale, 2020). It’s been used for decades to assess stroke damage and distinguish types of dementia, but mainstream psychiatry has never adopted it as a clinical tool.

Amen, however, who has a chain of six clinics across the US, says that after viewing more than 160,000 brain SPECT scans, he has discerned distinct blood flow patterns specific to common brain disorders including depression, obsessive compulsive disorder and drug toxicity. Rather than “flying blind” and basing diagnosis and treatment on symptoms, Amen argues that SPECT images give objective biological evidence that can make a big difference in treatment choice.

A number of studies, including a 2014 review of SPECT research, confirm its value as a tool in the diagnosis and treatment of a range of psychiatric conditions.6 One pilot study published in 2019 further indicates that SPECT can identify areas of reduced blood flow in the brains of children with learning disabilities.7

A 2015 study Amen coauthored with researchers including Andrew Newberg, a radiologist at Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, and Rob Tarzwell, a psychiatrist and assistant professor at the University of British Columbia, demonstrated that SPECT scanning could distinguish between traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – two conditions that have similar symptoms but very different treatment approaches.8

In 2018, Amen and colleagues published the largest study of brain SPECT scans to date – 62,454 in total. The researchers estimated the age of the brains as they

appeared in images (based on the fact that younger brains have greater blood flow) and compared this to participants’ actual chronological age and their risk factors. They found that brains were prematurely aged by an average of 4 years in people with schizophrenia, by 2.8 years in cannabis users, by 1.6 years in those with bipolar disorder, by 1.4 years in those with ADHD, and by 0.6 years in those with a history of alcohol abuse.9

Daniel Amen’s game-changing brain plan that turned injured brains around

In Daniel Amen’s study of 30 retired football players with brain damage and cognitive impairment from repeated head injuries on the field and substance abuse, the players were encouraged to lose weight and take nutritional supplements for six months. At the end of this time, 69 percent of them reported improved memory, 53 percent better mood and nearly half showed improvement on cognitive function tests and information processing times. Their supplement regimen included:

• Omega-3 fatty acids containing 1,720 mg EPA and 1,160 mg DHA

• A high-potency multivitamin/mineral supplement

• A “brain enhancement supplement” containing:

Ginkgo biloba. A 2016 review found “clear evidence” to support using Gingko biloba for mild cognitive impairment and dementia at a dose of 240 mg per day).1

Vinpocetine, a derivative of the periwinkle plant, used for stroke and dementia for more than 30 years. A 2019 review describes it as a potent anti-inflammatory with antioxidant and anti-blood clotting properties that enhances blood flow.2

N-acetylcysteine (NAC). This potent antioxidant was found to have few side-effects at an upper daily dose of 2 g (1,000 mg twice daily).3

Alpha-lipoic acid to improve antioxidant levels, taken in doses of 300-600 mg daily.

Phosphatidylserine, vital for proper nerve conduction and shown to slow, halt or reverse structural brain deterioration at doses of 300 to 800 mg per day.4

Huperzine A, which inhibits the breakdown of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter involved in learning. It is normally taken in doses of 50-200 mcg daily.

Acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR). This form of L-carnitine that crosses the blood-brain barrier has been shown to improve symptoms in mildly demented patients at a dose of 2 g per day.5

Correct blood flow

“Low blood flow in the brain is the number one predictor of future memory problems and Alzheimer’s disease and how quickly your brain will deteriorate,” Amen writes in Memory Rescue (Tyndale, 2017), and he insists that signs of low blood flow in the brain are visible on SPECT scans years if not decades before clinical Alzheimer’s sets in.

“If you have blood flow problems anywhere in your body, you probably have them everywhere,” according to Amen, whose protocols for Alzheimer’s are aimed at optimizing blood flow throughout the body.

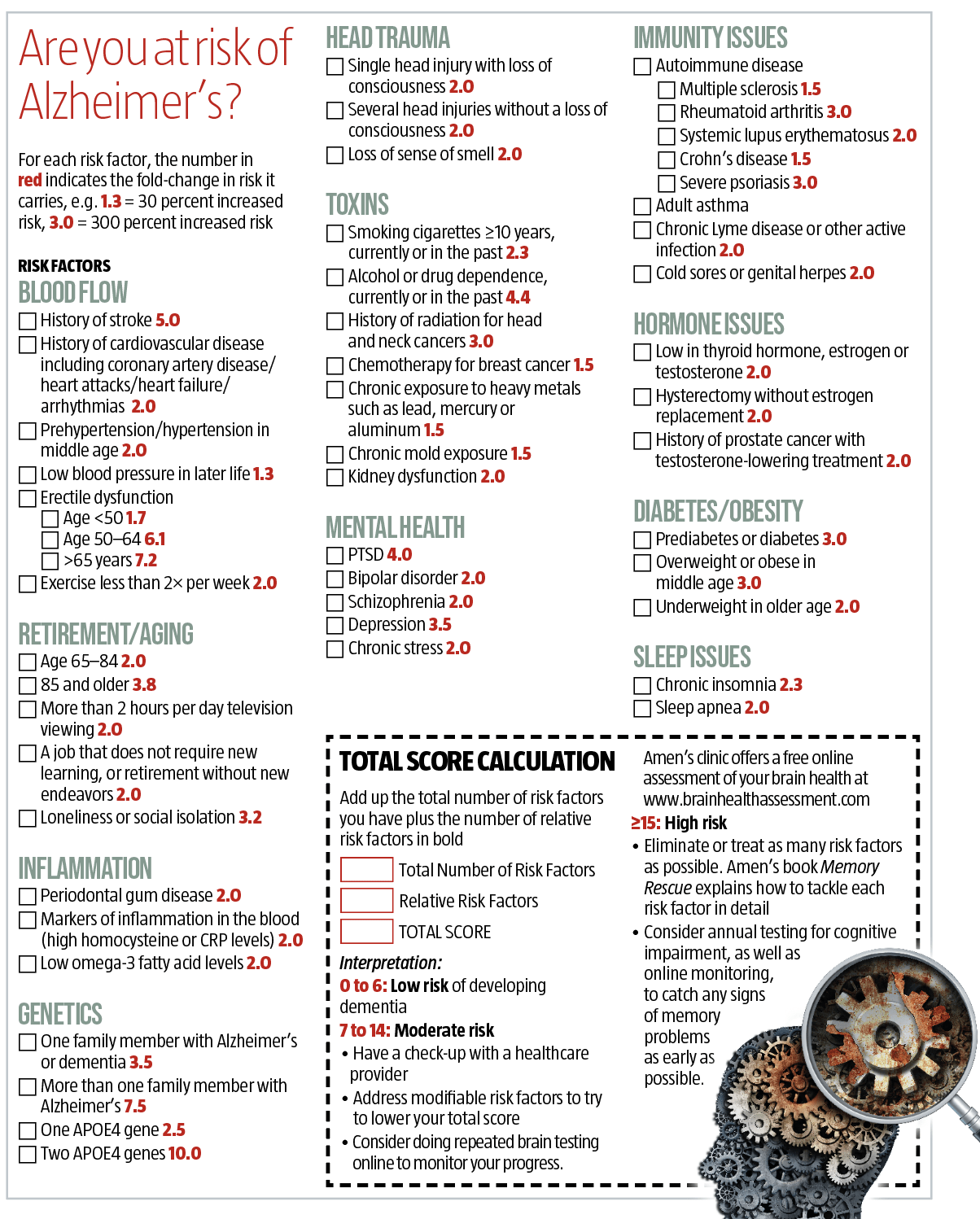

According to the emerging literature on nonpharmaceutical interventions, the key to staving off Alzheimer’s is to start as soon as possible and knock down as many of the individual health factors or habits that are elevating your risk as possible (see box, page 34). This includes increasing detoxification of environmental toxins such as aluminum while boosting brain-building habits that reduce risk.

Through this lens, mild cognitive impairment is seen as a critical window of opportunity for brain healing. You don’t need to image your brain to begin.

Seeking a cure

Harold Williams saw a few doctors following his initial diagnosis of cognitive decline and was offered prescriptions for drugs like Aricept (donepezil), but he declined because of their potential for nasty side-effects including nausea, vomiting and fatigue. He and his doctors also knew they would only postpone his symptoms for a few months at best.

In 2016, with Harold’s memory loss on a slide downhill, his wife Mary Ellen came across a nonprofit called Sharp Again Naturally founded by Lisa Feiner, a wellness coach, in 2013 to help people access and implement the emerging science on how to prevent and reverse cognitive decline. They were holding an information session about how to improve brain function without drugs. “It was the first time we ever heard there was something we might be able to do for Harold’s memory,” says Mary Ellen.

A few months later, the Williamses attended a weekend conference where a line-up of heavy hitters in integrative medicine presented new science on the brain, including the Cleveland Clinic’s Dr Mark Hyman, author of 12 bestselling books including Food Fix (Little, Brown Spark 2020), Dr David Perlmutter, the author of Grain Brain (Little, Brown Spark, 2013) and Dr Dale Bredesen, author of The End of Alzheimer’s (Avery, 2017).

Bredesen’s work in particular has been revolutionary in terms of reversing cognitive decline and treating Alzheimer’s. The reason that a single drug hasn’t worked for Alzheimer’s, he says, is because it is a multifactorial disease. Drugs that target one molecule will not address a problem that he compares to keeping a roof with 36 holes from leaking. You have to plug as many “holes” as possible, from diet to exercise to nutritional deficiencies. Amen has a similar risk analysis.

There are variations of brain health diets, but a big part of any of these protocols is eliminating sugar and processed and pesticide-laden foods that contain inflammatory oils (corn, canola and/or sunflower oil) as well as chemicals like monosodium glutamate (MSG) and Red Dye #40, which can trigger inflammatory storms in the brain.

A ketogenic diet, in which carbohydrates are low enough to flip the body – and brain – into fat-burning mode, has shown benefit,10 as has intermittent fasting, in which the body switches to fat-burning by fasting a minimum of 12 hours per day, as in Bredesen’s protocol. Perlmutter recommends eliminating grains including wheat and rice altogether, while Amen suggests eliminating foods linked to “leaky gut” and immune system activation such as gluten, dairy and soy at least for a month to see what impact it has on mind and mood.

The same diets are used to treat chronic inflammatory issues such as autoimmune diseases and diabetes, as well as heart disease. “I often tell patients, whatever is good for your heart is good for your brain. And whatever is bad for your heart is also bad for your brain,” Amen says

It isn’t brain cells that age rapidly as we get older; it is our blood vessels that age first. This means supporting the blood flow necessary for oxygenating and feeding the brain and clearing toxins is critical.

Harold and Mary Ellen Williams found a doctor who understood these concepts and had trained in testing for inflammation-related conditions, environmental toxins and the lifestyle changes to address them.

“Blood tests showed I had inflammation in my body and was deficient in certain nutrients,” says Harold. He ditched gluten and dairy from his diet, began taking supplements like B vitamins, omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin D, and started to exercise daily.

After one month, Harold started to see whole-body benefits. “I lost a little weight and my joints felt better,” he says. “After two months, my memory was much clearer, I could put thoughts together again and follow conversations. My diet had definitely improved, and I continued to lose weight.”

After six months Harold says that he had dropped 30 pounds that he’s kept off for more than four years and “felt the best I had in many years.”

Now 63, Harold thinks his life would be very different today if his wife hadn’t found Sharp Again Naturally. “I know that if I had not come across this information, I would have been diagnosed at the very

least with arthritis and dementia, I would be on several prescription medications, and I would be pretty socially isolated.” The changes he made, he says, were “lifesaving.”

Exercise your brain

Not exercising is a major risk factor for memory loss in large part because physical activity helps keep blood vessels healthy, and blood circulation is key to brain health, according to psychiatrist Daniel Amen.

“Exercise helps to boost a chemical called nitrous oxide, which is produced in the walls of blood vessels and helps to control their shape. If blood vessel walls do not receive pulses of blood flow regularly from exercise, they begin to distort, flatten out and limit blood flow overall. As a result the body’s tissues including the brain do not receive the nutrients they need or have a good mechanism to rid themselves of the toxins that build up in the body.” Additionally, regular exercise has been shown to:

• increase the size of the hippocampus, a brain area with a major role in learning and memory1

• stimulate cell growth factors that improve cognition

• exert anti-inflammatory effects and improve brain oxidative stress levels, thereby ameliorating the pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease.2

• maintain coordination

• increase strength and flexibility

• allow greater detoxification through sweat

• enhance sleep and immunity

• improve executive function.

Studies show that women who are physically fit when they’re middle-aged are less likely to develop dementia. If they do develop it, they get the disease much later – at an average age of 90, compared to 79 for women who are unfit.3

No matter what your age, research has shown that you can improve your brain function by exercise, but the type of exercise you choose is important.

HIIT it. According to one study, high-intensity interval training (HIIT, four sets of 4 minutes at high intensity on a treadmill) improved memory performance by up to 30 percent, while moderate aerobic workouts or stretching offered no significant improvement.4

Lift weights. Canadian researchers found that a group of 70- to 80-year-old women with mild cognitive impairment significantly improved their memory performance by strength training twice weekly over six months.5

Pick up a racquet. Racquet sports from tennis and squash to ping-pong have the advantage of giving your brain a workout as well as your body. Those who play are 56 percent less likely to die of cardiovascular disease – which affects brain function.6 Playing table tennis has been associated with better brain function than dancing, walking and even gymnastics.7

Are your medications robbing your mind?

Many medications deplete important brain nutrients, causing damage that leads to dementia-like symptoms. Psychiatrist Daniel Amen (The End of Mental Illness, Tyndale, 2020) says that when he began using SPECT brain imaging he could see the negative effects and reduced blood flow caused by certain pharmaceuticals like anxiety and pain medications. Here’s a list of the most common drugs that can cause problems. Be sure to consult your practitioner before stopping any medication.

Anti-diabetic drugs have been linked to decreases in coenzyme Q10 and vitamin B12 levels, which affect brain function. The antidiabetic drug metformin in particular has been associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.1

Anticholinergic drugs like Artane, Bentyl, Oxytrol, Neosol, Symax and Vesicare, used for a wide variety of conditions from urinary incontinence and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) to Parkinson’s disease, and even antihistamines like Benadryl, affect the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, important for memory and learning as well as other body functions such as heart rate and stomach muscle contractions.

One 2019 study by researchers at the University of Washington School of Pharmacy found that people aged 65 and older who used anticholinergic drugs were more likely to develop dementia than those who didn’t use them, and the larger the cumulative dose, the greater the risk. After three years or more, they faced a 54 percent higher dementia risk.2

Benzodiazepines including Valium and Xanax are the most commonly prescribed sedatives, typically used for insomnia or anxiety. Nearly one in 10 (9 percent) older Americans takes them, 31 percent of whom are long-term users. Several studies have found an association between long-term benzodiazepine use and dementia.3

PRINT ME OUT AND TAKE THE TEST!

|

References |

|

|

1 |

AMA Neurol, 2020: e202831 |

|

2 |

LSE Care Policy and Evaluation Centre, Projections of older people with dementia and costs of dementia care in the United Kingdom, 2019-2040. November, 2019 |

|

3 |

Alzheimer’s Association, Alzheimer’s and Dementia in Australia. www.alz.org |

|

4 |

US National Institute on Aging, Alzheimer’s Disease Fact Sheet. www.nia.nih.gov |

|

5 |

J Psychoactive Drugs, 2011; 43: 1-5 |

|

6 |

Indian J Nucl Med, 2014; 29: 210-21 |

|

7 |

J Postgrad Med, 2019; 65: 33-7 |

|

8 |

PLoS One, 2015; 10: e0129659 |

|

9 |

J Alzheimers Dis, 2018; 65: 1087-92 |

|

10 |

Int Rev Neurobiol, 2020; 155: 141-68 |

Are your medications robbing your mind?

|

References |

|

|

1 |

BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care, 2020; 8: e001370; J Am Geriatr Soc, 2012; 60: 916-21 |

|

2 |

JAMA Intern Med, 2015; 175: 401-7 |

|

3 |

J Clin Neurol, 2019; 15: 9-19 |

Exercise your brain

|

References |

|

|

1 |

Neuroimage, 2018; 166: 230-8 |

|

2 |

Ageing Res Rev, 2020; 62: 101108 |

|

3 |

Neurology, 2018; 90: e1298-305 |

|

4 |

Appl Physiol Nutr Metab, 2020, 45: 591-600 |

|

5 |

Arch Intern Med, 2012; 172: 666-8 |

|

6 |

Br J Sports Med, 2017; 51: 812-7 |

|

7 |

J Exerc Rehabil, 2014; 10: 291-4 |

Daniel Amen’s game-changing brain plan that turned injured brains around

|

References |

|

|

1 |

Front Aging Neurosci, 2016; 8: 276 |

|

2 |

Eur J Pharmacol, 2018; 819: 30-4 |

|

3 |

Expert Opin Biol Ther, 2008; 8: 1955-62 |

|

4 |

Nutrition, 2015; 31: 781-786 |

|

5 |

Int J Clin Pharmacol Res, 1990; 10: 75-9 |

What do you think? Start a conversation over on the... WDDTY Community